|

|

| |

|

Translation

into English by

Norman Henderson |

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

| |

Web:

Geir Neverdal (lektor/cand.philol) - Sel Historical

Society |

|

| |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Myths and

Legends? |

| |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

Background - The

Battle - Myths?

- Significance - Objects - Literature - Scotland

-

Programme2012 |

| |

|

|

| |

|

|

| |

|

|

| |

|

|

| |

“The bloody end to The Scottish March at Kringen is

one

of the occurrences in older Norwegian military

history most

shrouded in mystery and myth”.

(“Defence from

Leidang to total defence” by Ersland, Bjørlo,

Eriksen and Moland).

|

|

| |

|

|

| |

Contents of this page: |

|

| |

|

|

|

| |

Pillarguri?

What does Krag write about Pillarguri?

What do others write about Pillarguri?

Pillarguri or Prillarguri?

Lur or horn?

Was

Pillarguri a historical person?

The tales about “The

Mermaid” and weather calves

The timber avalanche

|

Berlin 1998

Kjell Fjerdingren

Lady

Sinclair

What happened to the surviving

Scots?

The Scot in

Gjerstad

The Scot who was saved by Ingebrigt Valde

|

|

| |

|

|

| |

Pillarguri? |

|

| |

|

|

| |

It is

difficult to distinguish between fact and fiction when

dealing with information handed down by word of mouth. (Snorre,

for example, based his works for the most part on

verbally transmitted

information, and much of what we read there today we

accept as being a factual description).

Today we can - with our knowledge - see that some of

what is told must be fiction. On other occasions there

can be a factual basis for what is told.

It is particularly difficult when what is being

recounted happened at a time when few contemporary

written sources existed.

The tale of

Pillarguri and her role in the battle at Kringen has

nevertheless made a strong impression on a great many

people - and she is one of the few characters in

Norwegian history known to large

groups of the population, and with whom they can

identify. She also became one of several symbolic

figures at the time of the dissolution of the Union with

Sweden in 1905.

It was not by chance that 83 emigrants from

Gudbrandsdalen in 1906 - one year after Norway became a

Sovereign state - gathered in Minneapolis to found a

Society, the main objective being to collect funds for a

new monument at Kringen. The symbol chosen was naturally

Pillarguri.

Nor was it by chance that it was King Haakon VII who

unveiled this Monument at the 300th. Anniversary in

Kringen in 1912. The Prime Minister was also present.

The symbolic value has been - and is - considerable. |

|

| |

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

| |

Angell

writes: |

|

| |

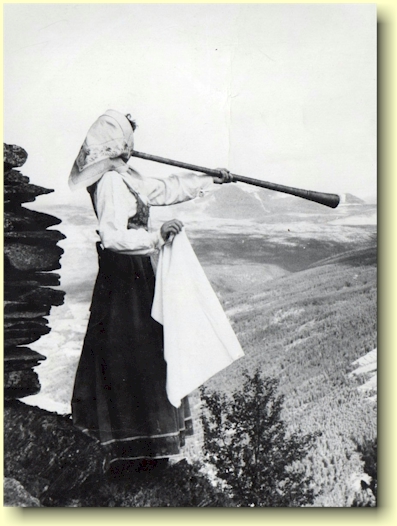

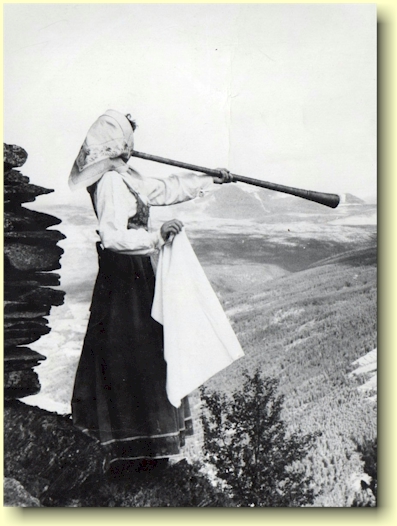

There was a girl in the village called Gudrid. She

was such an accomplished player of the

lure

and buckhorn (bukkehorn)

that she was given the name Prillar-Gudrid. She has

been much spoken of after that day and has become

etched in everyone’s memory”.

|

|

| |

The farmer at Storøya was not the only one who was

to give the signal. To be certain that everybody

knew the exact moment at which to act, that everyone

in the woods should be able to see the signal

clearly, a signal from Seljordkampen (Pillarguritoppen

- author’s note) should be made. Prillar-Gudrid

should hang a white cloth - some mean a length of

white woven wool material - over the sheer cliffside.

As the Scots advanced she would allow this woven

wool material to unroll showing the farmers how far

the Scots had come. The longer the piece of

material, the closer the Scots were. When she saw

the farmer on the white horse turn back quickly, she

should let the cloth fall. - Everybody should be

able to see that signal; nobody could hold back

then.

(It is also said that she had the cloth wound round

her arm and she should shorten it as the Scots

marched forward).

It was a double signal; a modern form of “semaphore”

if you will. Brilliantly thought out.

|

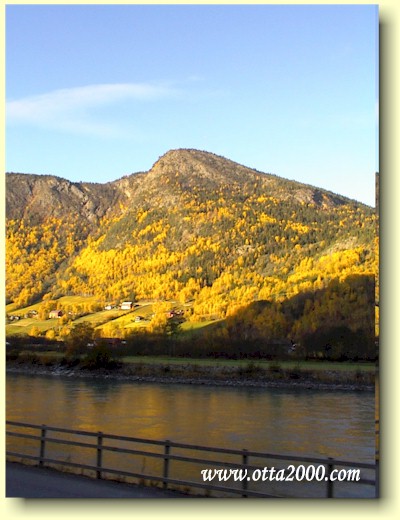

Pillarguritoppen

seen from a little north of Kringen. |

|

| |

|

|

|

| |

Many are also of the opinion that Prillar-Gudrid

should give the signal by playing a tune of her own

or a folk tune on the lure. In most people’s minds

this seems to be the case....

The image of the girl stood up there in the minds of

the dalesmen for a very long time - as she will

continue to do in the minds of all Norwegians in

times to come.

But Prillar-Gudrid had another task besides giving

signals. The leaders were afraid that the Scots

should find out about the ambush - because then the

battle would in all probability be lost.

|

|

| |

There are a number of stories about individuals who

took part in the Battle of Kringen and they should

be mentioned. First of all there is Prillar-Gudrid

(Pillarguri). She blew her lure for a long time

during the Battle, but when she saw that the river

Laagen became coloured red with blood she threw away

her lure, lay down and wept.

(Angell pp.64)

|

|

| |

|

|

| |

|

|

| |

|

|

| |

What does Krag

write about Pillarguri? |

|

| |

(Coming later)

|

|

|

| |

|

|

| |

|

|

| |

What do

others write about Pillarguri? |

|

| |

(Coming later) |

|

|

| |

|

|

| |

|

|

| |

Pillarguri

or Prillarguri? |

|

| |

|

|

|

|

|

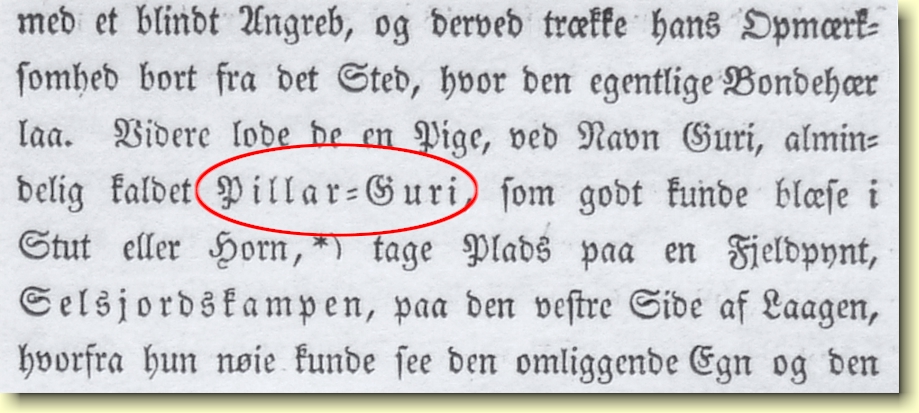

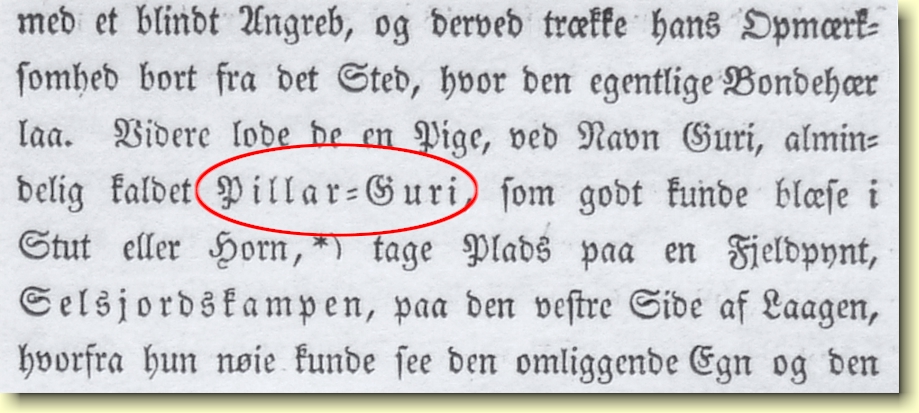

Krag,

the Vågå parson, who himself lived in the district and

collected the local tales, writes in his book from

1838 about “Pillar-

Guri”:

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

".. with a blind Attack, thereby taking his

Attention away from the place, where the real

Farmers' army lay. Furthermore they let a Girl, with

the Name Guri, commonly called

Pillar-Guri,

who could blow a Stut or Horn well, *) take up

position on a Mountain Peak, Selsjordskampen, on the

west Side of the Laagen, from where she could

clearly see the surrounding landscape and the ..."

|

|

|

|

Krag, 1838, page 35 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Andreas Faye

who, apart from his periods abroad, lived all his life

in Drammen, Christiania and on Sørlandet mentions in his

book from 1833 (according to genealogist

Lars Løberg):

“...both the girl and the farmer on the horse in his

publication of Norwegian Legends in 1833. He says

here that the legend about “Ragnhild or

Prellegunhild, (Lure, Prellehorn) has been told to

me

verbally. The legend about the man on the white

Horse ... in the same way, verbally."

In other

words he calls her “Ragnhild”

or “Prellegunhild”.

Magnus

B. Landstad (1802-1880)

- uses

the name

Prillar-Guri.

It is possible that his poem was written in connection

with the 250th. Anniversary in 1862, but we know little

about this. |

Ragnhild Glad as Pillarguri in 1962

(Thanks go to Bjørn Glad who gave us

the photo) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Krag is the one who, in the 1830s, came

closest to the source of this

information - and in local tradition she was

called

Pillarguri.

|

|

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

Lur or horn? |

|

|

| |

(Coming later) |

|

| |

|

|

| |

|

|

| |

|

|

| |

Was

Pillarguri a historic person? |

|

| |

|

|

| |

According

to local tales she was.

She occupies a strong position in the verbal tales which

Krag refers to in his writings of 1838 - and in the

account of The Scottish March she occupies a place as

part of the diversionary strategy decided

upon before the battle.

Doubt is raised from other quarters, also because she is

not mentioned in Storm’s Zinklarvisen - but neither are

Randklev, Hågå or Sejelstad.

Storm also

mentions only farmers from

“Vaage, Lessø and Lom”

in his folksong - those who came from the South, Fron

and Ringebu, and who played a major role at Kringen, are

not mentioned either.

Zinklarvisen definitely does not contain a detailed

description of what happened at Kringen.

|

|

| |

|

|

| |

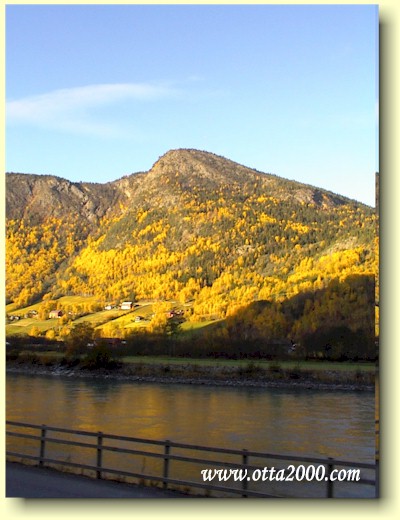

According

to local tradition Pillarguri was born and grew up at

Kruke in Heidal

Pål Glad

Kruke, who owns the farm today, has given us the photo

shown below.

You may read more about Kruke and its history here:

www.kruke.net

. |

|

| |

|

|

|

Kruke in

Heidal |

| |

(More about

this later)

|

|

| |

The

following is clear: |

|

| |

|

|

| |

The tale about Pillarguri and her role in the

battle at Kringen has made a strong impression

on a great many people - and she is one of the

few characters in Norwegian history known to

large groups of the population and with whom

they can identify.

She also became one of the symbolic figures

around the time of the dissolution of the Union

with Sweden in 1905.

|

|

| |

|

|

| |

|

|

| |

|

|

|

| |

The tales of “Havfruen”

(“The Mermaid”) and

“veirkalvene” (“weathercalves”) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Imagination

has been allowed to run riot here.

|

|

| |

|

|

| |

|

|

| |

|

|

|

| |

The timber avalanche |

|

|

|

(Coming later) |

|

| |

|

|

| |

|

|

| |

|

|

| |

|

|

| |

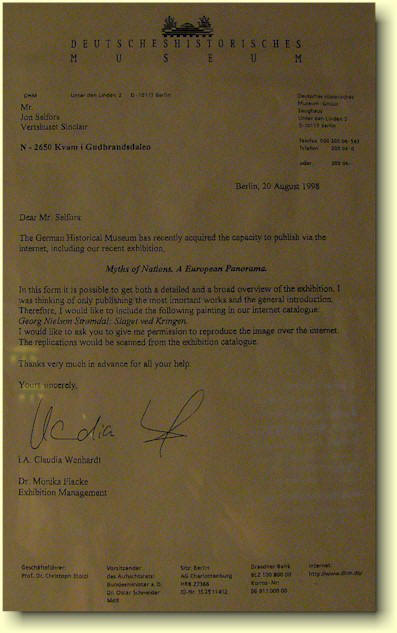

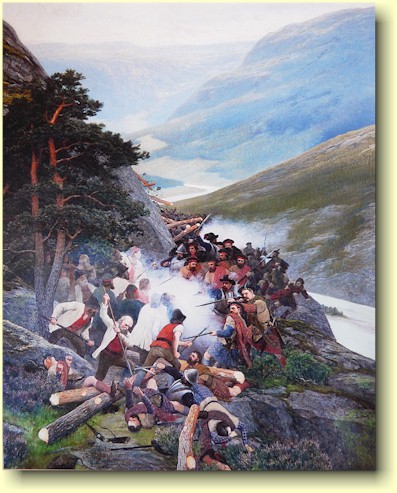

Berlin 1998

- An

exhibition portraying European historical events to

which a great degree of myth is attached. The exhibition

was arranged by Deutsches Historisches Museum. |

|

| |

|

|

|

| |

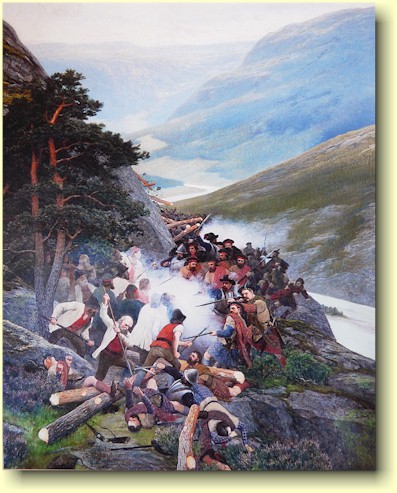

When

Deutsches Historisches Museum in Berlin planned the

arrangement of this exhibition, Georg Strømdal’s

painting from Kringen was chosen to

represent Norway.

The Museum

considered the following episodes from Norwegian

history, as well as Kringen:

Leiv Erikson’s discovery of America

The Battle of Stiklestad in 1030

The Battle of Stanford Bridge (England) in 1066 and

The National Assembly at Eidsvoll in 1814

Jon Selfors

currently takes care of the painting for future

generations. It is part of The Scottish March Collection

at Kvam in

Gudbrandsdalen.

A letter

from Dr. Monica Flacke in Berlin

(GD

17.th June-97)

states that, in addition to Strømdal’s large Kringen

painting, the exhibition would also display other items

illustrating the fight

between the farmers and the Scottish mercenary soldiers,

e.g. illustrations, folk literature, song books,

postcards, coins and medals. |

Kringen

Georg Strømdals (1856-1914) maleri fra 1897 |

|

|

|

According to

the same newspaper-cutting from GD, the then

“forbundskansler Helmut Kohl, was the Museum’s and

exhibition’s Patron”.

After the

exhibition the museum in Berlin requested permission to

publish a reproduction of the painting on their new

Internet pages.

(The Internet was a relatively new medium in 1998) |

|

| |

|

|

|

| |

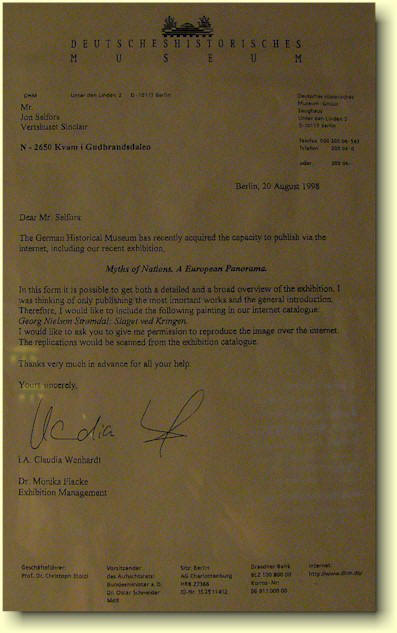

(Letter from)

Deutsches Historisches Museum ...

Dear Mr Selfors;

The German Historical Museum has

recently acquired the capacity to publish via the

Internet, including our recent exhibition,

Myths of Nations. A European

Panorama.

In this form it is possible to get

both a detailed and a broad overview of the exhibition.

I was thinking of only publishing the most

imortant (sic)

works and the general introduction.

Therefore, I would like to include the following

painting in our internet catalogue:

Georg Nilsen Strømdal: Slaget ved Kringen

(the Battle of Kringen).

I would like to ask you to give me permission

to reproduce the image over the internet.

The replications would be scanned from the exhibition

catalogue.

Thanks very much in advance for all your help.

Yours sincerely,

(Sign.)

i.A. Claudia Wenhardt

Dr. Monica Flacke

Exhibition Management

|

Click to get a larger version of the letter. |

|

| |

|

|

|

|

Text

taken from the

Berlin museum’s Internet page (English version): |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

The Battle of Kringen, 1612

"The Battle of Kringen in 1612 was basically an

episode of little consequence during the Kalmar War

(1611-1613) between Denmark and Sweden. Norway,

which was a province of Denmark, was drawn into the

war when the Danish king, Christian IV, demanded

that the Norwegians supply an army of 8,000

peasants. Mass desertions began as soon as the

troops began to assemble. The reason the peasants

deserted, according to 19th century historians, was

their love of freedom and attachment to their native

land, which they placed above their loyalty to the

crown. It was not until an army of some 900

(the correct number was

300-350)

Scottish farm labourers serving for

the Swedish king landed on the Norwegian coast on

their way to Sweden that the Norwegians took up arms

and defeated the invaders near Kringen in the

Gudbrandsdal valley.

The memory of this victory – and thus of their

contribution to the Danish triumph over the Swedes –

enhanced the Norwegians' national pride in the 19th

century. An important part of this tradition is the

idealisation of the Norwegian peasants, their

courage, their cleverness in fighting and above all

their love of freedom. Hand in hand with this image

was the glorification of the Norwegian mountains as

the home of an intensely freedom-loving, proud and

daring people. So the pictures of the event are as

much a monument to the mountainous landscape as they

are to the battle itself ..."

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Kjell Fjerdingren |

|

|

| |

(Coming later) |

|

| |

|

|

|

|

Lady Sinclair |

|

|

| |

(Coming later) |

|

| |

|

|

|

|

Man on the horse

(Storøya) |

|

|

| |

(Coming later) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

| |

|

|

| |

What

happened to the surviving Scots? |

|

| |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

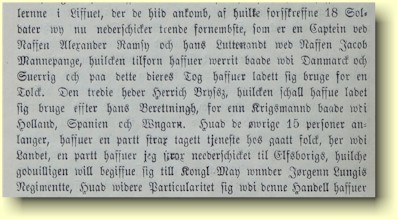

Governor

Kruse writes a little in his report about the 18

Scots who were brought to Akershus (Castle). He sends

the three most distinguished (the officers) to

Copenhagen. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

“ with regard to the remaining 15, some of them

immediately took work with the good people here (in

Norway) and some who as volunteers, will enter the

service of the King in Jøgenn Lungis’ regiment, I

sent immediately to

Elfsborg”

(somewhat freely translated from Governor

Kruse’s report to the Danish Chancellor).

Photo of

the report - Krag’s copy-->

|

|

|

|

|

There is

however a large number of stories about Scots who

survived - and who, for shorter or longer periods,

remained in Gudbrandsdalen and other places in Norway.

It is claimed that several of them were the originators

of new family trees surviving in Norway today.

If these accounts are to be accorded credibility (?),

there were several survivors from this confrontation. |

|

| |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

The Scot at Gjerstad

Gjerstad

historielag (Gjerstad Historical

Society) will in the Spring (2006) erect

a monument at the grave of a Scottish

mercenary soldier, according to

NRK-Sørlandet.

“The soldier came to Gjerstad after

fleeing from the historic battle at

Kringen in Gudbrandsdalen in 1612.

This is the battle which created the

story about Pillarguri.

The soldier’s grave in Gjerstad has

been unknown to most people.

But the Historical Society wants to

have a fitting monument to

Sinclair’s soldiers, says Olav

Vevstad in Gjerstad Historical

Society”.

NRK Sørlandet

Gjerstad kommune is close to

Risør ->

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

“The soldier

who was killed in Digerdal was one of two who came to

Telemark after the majority of the soldiers under the

command of the Scots Captain Sinclair had been killed by

farmers in Gudbrandsdalen in 1612. ...

While the one soldier fell in love with a girl from Bø,

the other wanted to return to Scotland.

He made his way towards a port in Sørlandet, but never

reached there.

He was found dead in the snow in Digerdal. He was buried

in Digerdal and the grave marked with a round stone at

each end.

For those who wish to visit the grave, the way is marked

from the main road to Digerdal”.

(Thanks go to Gjerstad Historical Society for the loan

of the photograph and text.) |

From

the unveiling of the commemorative tablet in

August 2006. In co-operation with Statskog, Gjerstad

Historical Society has ensured proper marking

of the old grave. |

|

| |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

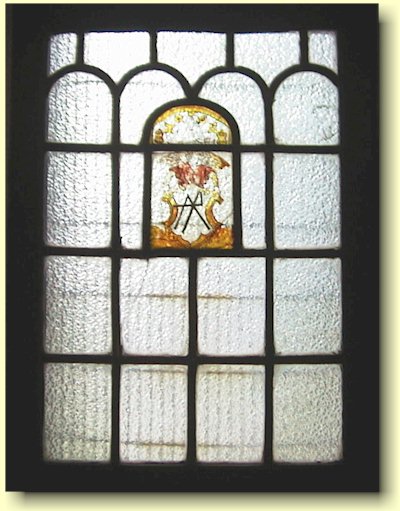

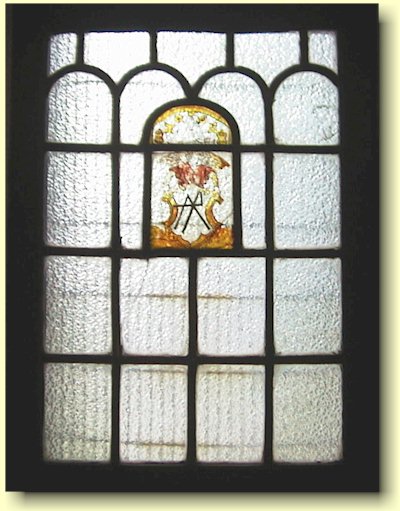

The Scot

who was saved by Ingebrigt Valde

Krag writes (p.28):

“The saga tells that One of the surviving Scots,

when he saw the Rifle pointed at him, ran to

Ingebrigt Valde from Vaage*)

and with Beseeching Gestures, begged for his Life

and Rescue and sought Shelter under his Horse,

whereupon Ingebrigt raised his Axe in his Protection

with the Threat that he would cut down whoever

killed him. This Scot was reportedly a Master glass

worker and later settled in

the Country and to Prove his Gratitude sent several

Windows to Ingebrigt Valde, whom in his Letters he

always referred to as his “Lifefather”. Of these

same Windows, one is still shown on Valde, in

which some decorations with etched work on a Rough

Shape, which represents a Shield, on which can be

seen a Mark like a Signet (perhaps Ingebrigt Valde’s)

and an Angel which seems to hold its hands in a

protective manner over it”.

*)

Hjorthøy calls him Ingebrikt Sørvold; in Grams

Mandtal (Grams Census) neither this name or

Ingebrikt Valdes is to be found, on the other hand

the tenant farmers Oluff and Knud Valde are both

named.

|

Thanks go to Ivar Teigum for the loan

of the photograph |

|

|

|

Where he

settled is not known, but the window is to be found

today in St. Edmund’s Church in Oslo. It was brought

there from Valle in the late 1800s

(Teigum2,

p.116) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

The farm

Skottelien in Vågå

This farm

was reportedly “first cleared by one of the remaining

Scots and thereafter given the name Skottelien”

(Lassen p.16) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

The farm

Skotte in Sel

“Called this

because it was cleared by one of the Scottish prisoners

who stayed (in the country)”

(Lassen

p.18) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| |

(More about this later) |

|

| |

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

| |

|

|

|

Background - The

Battle - Myths?

- Significance - Objects - Literature - Scotland

-

Programme2012 |

| |

|

|

| |

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| |

Skottetogsidene ble lagt ut på nettet 12. november 2010.

Denne siden ble sist oppdatert:

08. april 2012

Web:

Geir Neverdal (lektor/cand.philol) - Sel Historielag

www.otta2000.com

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|